Director: Werksmans Attorneys.

Continued pressure on business and world economies due to the ongoing battle with the Covid-19 pandemic continues into the second half of 2021 and looks set to continue into 2022. With recent unrest in parts of the country, many businesses had to shut down, with many of these failing to reopen.

Recently published figures by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) reflect an increasingly worrying trend of increased liquidations of companies and insolvencies for individuals. The total number of liquidations of companies increased by 21,5% in the first seven months of 2021 as compared with the first seven months of 2020. Further, insolvencies of individuals increased by 784,4 % (from 32 to 283 cases) in June 2021, as compared with May 2021. This is a staggering increase and where South Africans are clearly feeling the strain of ongoing shutdowns, and constraints imposed by deteriorating trading conditions caused by the impact of Covid-19 on our economy.

Factors which might point towards a pending liquidation

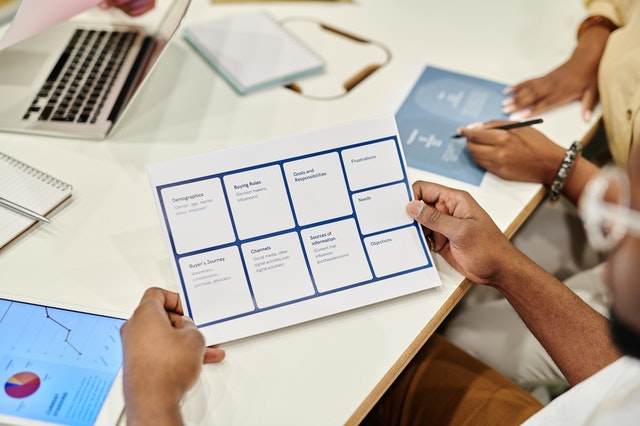

Creditors and suppliers of goods and services to companies in distress or which are on the cusp of insolvency have difficult decisions to make. Defaulting companies might already be struggling to pay existing debt, and where, without ongoing lines of credit, will not be able to continue trading. Management and credit controllers will need to keep a very careful watch on their customers and establish whether there are any warning signals of looming insolvency. Factors which might point towards a pending liquidation and an increased risk for a default include:

- Downward trend in entity’s share price (listed company);

- Commitments to pay long outstanding debt which are not met, and a general failure to pay accounts/creditors on time (exceeding credit limits consistently);

- An insistence on a renegotiation of contractual terms of supply;

- Artificial valuation of assets to increase value in balance sheet numbers;

- The existence of fraud (dishonesty) at management or employee level; and a refusal or failure by senior management to explain or remedy the potential for ongoing fraud;

- A switch over by suppliers to the company from the supply of goods on credit to a cash only supply;

- Multiple giving of security over the company’s debtors book (cession of debtors) in order to secure the ongoing supply of goods on credit;

- Receipt of letters of demand and summonses (court action), together with an increase in litigation and possibly judgements being taken against the company;

- Adverse credit ratings for the distressed company;

- Being placed on the corporate watch list at banks;

- A continued need for the company to call on its shareholders to inject working capital or equity into the business;

- An increased need for long term financing for short term cash flow requirements, coupled with adverse audit reports, negative cash flow, and an insolvent balance sheet;

- Management insisting on a reduced working week, lack of staff morale and reduced levels of motivation;

- Forcing employees to take unpaid leave;

- Industrial action, strikes and unrest at the workplace;

- Inability on the part of management and the board of directors to make important strategic decisions at critical times and which results in ineffectual leadership by the board. This might include irregular or no contact by board members with key executive staff; absence of directors from board meetings; worsening of relationships between directors and management and resignations at board level;

- General neglect and incompetence of management – including a lack of financial controls and failure to independently verify and safeguard the integrity of financial reporting;

- Inability on the part of the company to adapt to changing market conditions – such as a growth rate less than the inflation rate; inadequate review and analysis of ongoing errors and mistakes being made by management; significant loss of market share; exchange rate and commodity price fluctuations; and an increased risk of default as a result of adverse market and trading conditions;

- Loss of key personnel – losing critical staff can be the downfall of the business;

- Deterioration in relationships with bankers and financiers and where there is an ongoing need by these lenders to monitor levels of credit and overdraft facilities;

- Regulatory and legal compliance – environmental or corporate governance compliance; making provision for contingent liabilities as a result of non compliance; uncertainty created by law suits; change in government policy; adverse opinions of auditors; unforeseen security issues and national catastrophes such as unrest in a particular sector; and

- A refusal on the part of directors to provide deeds of suretyships/guarantees to suppliers of goods on credit.

Photo By: Darlene Alderson via Pexels

Often, when any one or more of these warning signals are prevalent, there is a fairly good chance that the company will have to file for business rescue, or alternatively for liquidation.

Chapter 6 of the Companies Act No. 73 of 2008

Chapter 6 of the Companies Act No. 73 of 2008 (“the Act”) introduced mechanisms to rescue those companies that are trading in financial distress and by way of the business rescue process. Suppliers and creditors that do not understand Chapter 6 of the Act and the intricacies of the business rescue mechanism, place themselves under severe risk in the event that one of their major customers (debtors) files for the business rescue process and where the rescue legislation intervenes and complicates ongoing business and trading relationships.

In South Africa, 2021 has seen several companies going out of business and with many turning to the business rescue process. South African creditors should realise that business rescue (as a restructuring tool for severely distressed companies) generally provides a “better” outcome than liquidation, and thus should seriously consider supporting the process. Unsecured suppliers/creditors facing the liquidation of its customer would in all likelihood receive a zero (or negligible) dividend after all secured and preferent creditors have been paid in liquidation. Generally, business rescue dividends should result in a higher return for creditors than would result in a liquidation.

It has however been recently reported that certain suppliers/creditors are becoming increasingly unhappy with the level of pay-outs/dividends that are generally being made available in the formal business rescue process. An example of this is the recent court action instituted by ten Edgars suppliers and in order to improve their low pay out and further to obtain clarity as to why the clothing retailer collapsed. Suppliers are unhappy with the business rescue dividend currently on offer and where they are owed a collective R109 million and where the plan offers approximately R7million to them as a pay-out. Secured creditors such as landlords and banks will receive a business rescue dividend of 19 cents in the Rand, whereas clothing and product suppliers, a pay-out of 6 cents in the Rand. The company and its business rescue practitioners have defended their position and where they reiterate that the business rescue plan was approved by 80% of creditors voting in accordance with the value of their claims as far back as June 2020. As this litigation has just commenced, one will have to follow the outcome in due course.

Photo By: Cytonn Photography via Unsplash

The South African business rescue process

Overall, the South African business rescue process is robust and effective and can result in positive outcomes for all stakeholders. In 2021/2022, we expect to see continued support on the part of suppliers and creditors for the business rescue process and which should continue to see companies being rescued and where there is a sustainable business model for ongoing trading. Ultimately, a company which is rescued provides an ongoing source of revenue for those suppliers that have supported a rescue process, and which results in the survival of its trading partner into the future. Examples of successful business rescues include Pearl Valley Golf Estate, Advanced Technologies and Engineering Company (ATE), Meltz Success, Moyo Restaurants, South Gold Exploration, Ellerines, South African Calcium Carbide, Edcon, Group 5, Basil Read, Consolidated Group, New House of Busby, SAA, and Comair. These rescue processes have all contributed to a renewed vigour in the business rescue space and in renewed confidence in the possibility of successful outcomes. Many of these companies have exited from the business rescue process with new owners and where the company has been given the opportunity to continue trading.

It appears that generally, South Africans have accepted that business rescue is a viable alternative to liquidation and one which supports job preservation and the ability to bring distressed companies back from the brink of liquidation, and to a position where such companies can continue to contribute to the South African economy.

Eric Levenstein is a Director at Werksmans Attorneys