The Battle of Alesia was a turning point in the Roman-Gallic Wars. After a few victories by the Gallic Confederation, their army (led by Vercingetorix) took refuge in the heavily fortified town of Alesia. Their hope was that they would hold out a siege by the Romans who would eventually return to Rome. The Roman Army (led by Julius Caesar) made their own fortifications around the town which cut off supply lines to the Gallic Confederation’s Army. It was now a case of what would happen first, would the Romans get bored and leave or would the Gallic Army suffer the pain of a slow death?

The Romans won because they were patient, well provisioned, and had superior (innovative) tactics. Vercingetorix was captured by the Romans, and Caesar returned to Rome a hero.

If we take the Romans tactics, and translate it into innovative business models, we see that they often overcome the challenges of disruptive environments because they are agile enough to adapt to change. Tactics that are not agile suffer the same fate as the Gallic Army, a slow death.

The most pertinent example of this is in the entertainment space. Traditional media sources such as books, magazines, satellite television networks and film production companies are facing major disruption from streaming services and online access platforms such as kindle.

Netflix and the death of Hollywood

The article points out that Netflix, is doing something beyond just centralizing distribution and production. It is also deliberately losing money.

This is a very dangerous practice. In the old system, studios sold content, often over-priced, often shoddy, but they sold it to people who bought it. The end network, either theatres or TV stations, had to choose from distributors what content to offer to customers. They had to make money to stay alive. They had to follow one of the basic rules of existing competition policy, which is that combining inputs into a final output should create a profit, an indication that the business agent has in some way generated something of value. This means that if you build a better mouse trap, or in this case, a movie or show people want to see, you can get it to market and sell it.

The article points out that Netflix violates this rule. Despite its claims of accounting profits, Netflix is a massive money-loser, projecting it will burn through $3.5 billion in cash just this year. Netflix is taking inputs and combining them into something that is of less value than those original inputs. But the company doesn’t really care if people watch its content, because it doesn’t sell content. The company is selling a story to Wall Street, that, like Amazon, it will achieve dominant market power. The story is that users will buy Netflix streaming services and it will be too much trouble to switch to a different service, which is a variant of a phenomenon called “lock-in.” So no one will be able to compete, the company will be able to raise prices and lower costs, and voila, another Amazon-style monopoly. It will be one of the few left standing after the inevitable shake-out.

To sell this story to investors, the company is interested only in adding subscribers, resulting in a set of choices whereby it underpays creators, and under-delivers for existing subscribers. And it still burns through money, but it can do so as long as it can sell its debt into the marketplace and its stock remains high. This creates an impossible burden on anyone who wants to make art and sell it in competition with Netflix, be that person an artist or a major studio; it’s simply impossible to compete at making better goods and services if your competitor can lose money indefinitely. Again, artists don’t notice this problem, because they like selling to Netflix. But they will notice, as Netflix’s strategy of underpaying them becomes more obvious.

Concentration Creep: Netflix Rebuilds the Studio System

The article points out that,Netflix, aside from losing money, has also slowly reconstructed the old vertically integrated studio system. The company is an integrated production and streaming service; if you want to distribute through Netflix, you work increasingly on Netflix’s terms, and vice versa. And Netflix pushes whatever content it wants at Netflix users, based on whatever algorithm it chooses. This is a similar story as Amazon, which spends large amounts of money on content, with content being a mostly minor part of its otherwise massive business. These are long-term predatory pricing plays, with predatory pricing meaning selling below cost to acquire market power, a practice that used to be illegal prior to the 1980s. Of course, these rules are not absolute; powerful creatives still have leverage, but the broad middle of creators do not.

Photo By: Cameron Venti via Unsplash

Netflix and Amazon are driving what can be called concentration creep across the industry. Concentration Creep means that consolidation in one part of an industry causes consolidation in other parts. Disney, for instance, is trying to mimic Netflix by launching what may be a below-cost streaming service. It also bought Fox’s media assets, so it can bulk up and gain market power. And Trump’s Antitrust chief, Makan Delrahim, is considering getting rid of the Paramount Consent Decrees, which might prompt Amazon or Netflix to simply buy a movie theatre chain.

The article adds that it is becoming increasingly clear that the only goal now in Hollywood is to gain market power in distribution or must-have content production, and then use that monopoly power to reduce the quality of output and reduce the bargaining leverage of artists. Even the agents, who are supposed to represent artists, are getting into the vertical integration game. The net effect is higher prices, less pay to artists, a less creative industry, and ultimately, the death of the Hollywood ecosystem of storytelling.

Such a dynamic isn’t just a problem in terms of a more arid artistic world but is a political and national security problem. We learn a lot from our movies and TV shows, including about politics and geo-politics. The U.S. military tends to subsidize movies that make them look good; with fewer producers of movies, such subsidies will have more impact, and perhaps make it less likely artists criticize the state or powerful corporations. But the free expression problem imports overt government censorship into America and the entire West.

The centralization of power in a few studios and chains is global. In 2015, the U.S.-China Security Review Commission noted that Hollywood now obeys Chinese censors pretty much all films, even those made and distributed solely in the West. Unless this system is restructured, it is unlikely we will see any critical depictions of Chinese government actors again, which has parallels to the Studio System in the 1930s pandering to Nazi Germany.

Can Hollywood Be Saved?

So what now?

The article points out that, earlier this year, billionaire Barry Diller pronounced Hollywood irrelevant. In the old days, six companies controlled the market. And if someone else got big enough to matter, a studio bought the new player. “In other words,” he said, “it used to be if you could get your hands on a movie studio, you were sitting at a table with only five other people.”

Today, Amazon and Netflix are too big and powerful to be bought and have found a way to produce and distribute content that studios can’t touch. “Those who chase Netflix,” he said, “are fools.”

The article adds that this is a very billionaire-y perspective, and like all billionaires who made their money in the 1980s, Diller chooses to ignore the impact of public policy on industry structure, and how power was broadly shared. But there’s a grain of important truth in what he’s saying. The old system is falling apart, and a new far more concentrated one is emerging.

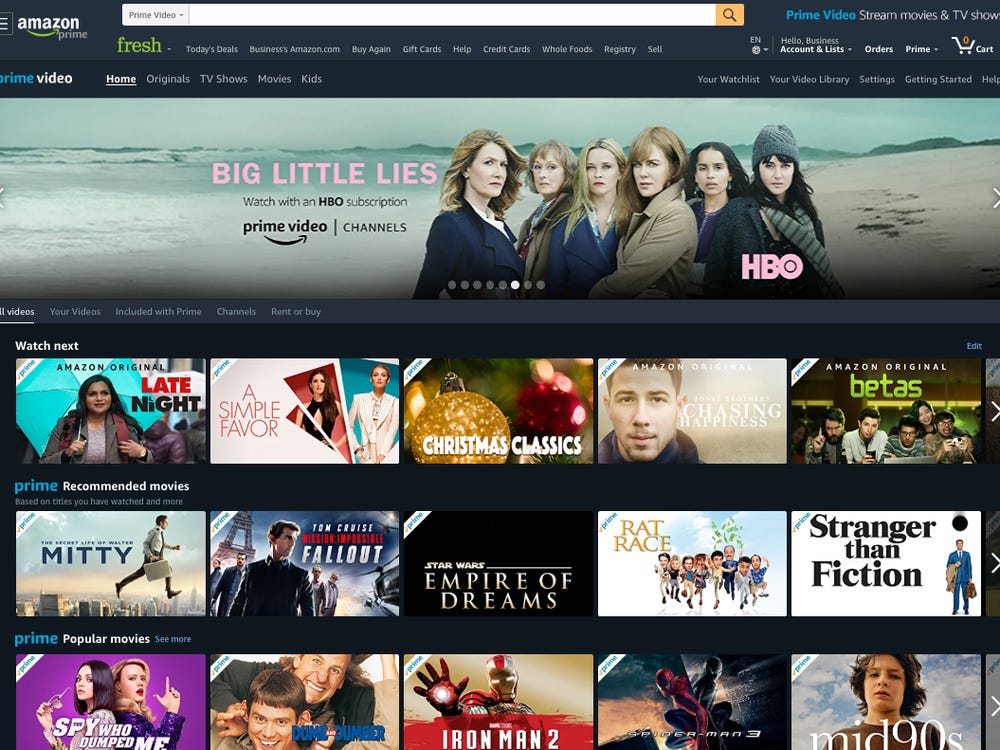

Photo By: Amazon Prime Video

The article points out that there is no reason we have to build a highly concentrated storytelling industry on top of the internet, which used to be the most decentralized communications technology ever imagined in human history. The answer to the question of whether Hollywood can be saved is a resounding YES. Fundamentally, streaming is a commodity service; Netflix isn’t anything special, it’s just a good infrastructure service which has morphed into a monster attempting to control our access to content. Disney is just trying to become a monopoly studio of branded must-have content and reproduce Netflix’s power. Movie chains are too big. And so on and so forth. These are all just political choices.

In other words, we should aim to restore open markets for content again. This means separating out the industry into production, distribution, and retailing. We should probably ban predatory pricing so Netflix isn’t dumping into the market. And we should probably begin a radical decentralization of chains and studios. This is all possible. We’ve done it before, and we can do it again. I love movies, and I think Hollywood is worth saving. And while I wouldn’t recommend The Hangover III, great comedies help us see ourselves as the absurd creatures that we really are.

Thanks for reading, and if you enjoy this newsletter, please share it on social media, forward it to your friends, or just sign up here.

The real lesson

The real lesson behind the rise of Netflix and Amazon….and now Disney+ and HBO Max, is that the rise of these streaming services, and the death of Hollywood and the old system, is a result of identifying a growing customer demand, and serving that demand.

Social distancing global lockdowns confined 70% of the world’s population to quarters for long periods during 2020 and 2021. During this time, the consumer turned to satellite television companies and got annoyed with the endless repeated content and the promise of new content in Summer or Winter. The modern consumer is obsessed with instant gratification and naturally gravitated towards services that offered immediate access to premium content with zero chance that there will be a repeat of that content unless the consumer choses to do so.

Disruption, in this case, came in the form of a global pandemic which accelerated a need for innovative business models such as Netflix and Amazon Prime. This need was always going to arise, it was just a matter of when. If anything, Netflix and Amazon Prime showed the value of being early adopters when it comes to disruption.