When tasked with improving a company’s value proposition, CEO’s often turn to the financial aspects of the company trying to find ways in which certain enhancements can be made to add value. However, the past three years has shown us that adding value is about enhancing the customer experience, which often has very little to do with the financial aspects of a company.

But what are these elements? A recent article by PwC provides more insight into this. We will focus on the first two elements in this article.

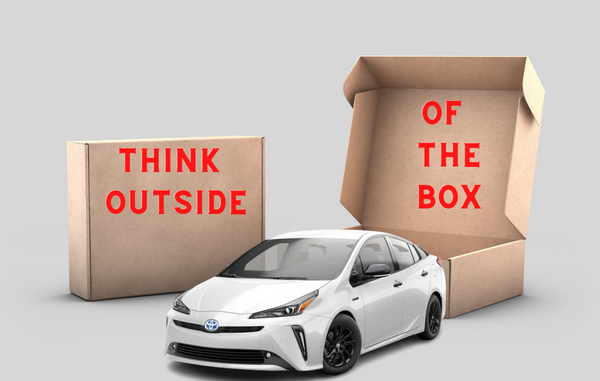

Apply “visionary valuation” — along with ongoing measurement and correction

The PwC article points out that, if a strategy is disruptive — take Toyota’s launch of the Prius two decades ago, as a bridge to electric vehicles, or Apple’s creation of the tablet market with the iPad — it can be difficult or even impossible to measure its value creation potential with any certainty prior to execution. In fact, any attempt could end up blocking innovation and, ultimately, value. Instead, leaders should look to achieve a “visionary valuation” by clarifying the forms of value they’re trying to create, understanding how commitment to those types of value will drive enterprise value, and developing a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) to track value creation across this broader ecosystem. Then, while executing the strategy, the business should measure the outcomes continually, using the results to recalibrate, course-correct, or even replace the strategy, and to report, listen, and respond to stakeholders in a feedback loop.

Organizations need to do these things against a global backdrop in which both the destruction and the creation of value, including value-associated issues such as climate change and social upheaval, are accelerating. In such an environment, the only way to communicate effectively with stakeholders is by translating critical corporate priorities through a value lens and representing the effects of strategic decisions and subsequent actions in a unified value framework. Such a framework will reinforce linkages between a company’s purpose and its strategy; between its strategic priorities and transparent reporting of all its results, including nonfinancial ones; and between its agenda for corporate transformation and societal renewal. It also will help communicate interconnections within the value creation ecosystem and clarify enterprise value drivers that historically might not have made their way into a calculation of net present value.

Photo By: Canva

The article adds that Unilever puts sustainability at the heart of its strategy. An instance of a business making these linkages explicit arose in December 2020, when global consumer products giant Unilever announced it would put its climate transition action plan before shareholders for approval, reportedly becoming the first major global company to take such a step. The move strongly underlined the convergence of the shareholder and wider stakeholder agendas. Unilever CEO Alan Jope commented, “We have a wide-ranging and ambitious set of climate commitments — but we know they are only as good as our delivery against them. That’s why we will be sharing more detail with our shareholders, who are increasingly wanting to understand more about our strategy and plans.”

In measuring and reporting on its progress on reducing carbon emissions, Unilever says it will continue to take an iterative and transparent approach, updating its plans on a rolling basis in response to outcomes and being clear about challenges across its value chain.

The article points out that this approach echoes the company’s strategy over the past decade with its Sustainable Living Plan. Launched in 2010, the plan targeted three objectives, each aligned with the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals: First, improve health and well-being for more than 1 billion people by 2020; second, halve its environmental footprint by 2030; and third, enhance the livelihood of millions of people by 2020. Marking 10 years of the plan in May 2020, Jope stressed the iterative nature of the company’s actions in response to its KPIs: “As the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan journey concludes, we will take everything we’ve learned and build on it. We will do more of what has worked well, we will correct what has not, and we will set ourselves new challenges.”

By aligning its purpose with that of its customers and consumers, Unilever strengthens its reputation and brand value — and avoids alienating its customer base and destroying value.

Like several other companies, Unilever also undertook a high-level assessment of the potential material impacts on its business arising from the 2- and 4-degree Celsius global warming scenarios for 2030. Its analysis confirmed that both scenarios presented financial risks to its business, including rising costs of raw materials and packaging in a 2-degree rise and chronic water stress and extreme weather in a 4-degree rise. For Unilever, the assessment confirmed the importance of understanding the critical business dependencies of climate change and having plans in place to mitigate risks and prepare for the operating environment of the future.

Think like a disruptor

The article points out that, to rethink strategy in the face of disruption, businesses in any industry can ask: If we were coming into this marketplace today as a new entrant, unburdened by legacy infrastructure and assets, what strategy would we adopt? This blank-slate mindset enables leaders to anticipate new competitive threats and opportunities and potentially formulate, evaluate, and fine-tune a strategy that could turn them into actual, not hypothetical, disruptors.

Organizations that have fully deployed and executed a blank-slate strategy are few and far between. But among those that have, several have succeeded in creating sustainable new operating models that have significantly boosted enterprise value — and some are extending that value creation far across their ecosystem. We’d suggest, in fact, that the gathering force of the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) imperative will create enormous opportunities for disruption and self-disruption, just as the digital revolution did.

The PwC article adds that Netflix and Qantas self-disrupt. Take Netflix, which has disrupted its industry twice and itself once: first by launching a DVD mail service against incumbents such as Blockbuster and then by switching to streaming in 2007 and production of in-home entertainment in 2012. The second strategy, in particular, delivered. In the third quarter of 2010, Netflix’s market value was $8.75 billion. A decade later, it was $233 billion.

Another prominent example of blank-slate self-disruption was the launch of the low-cost airline Jetstar in 2003 by the Australian incumbent Qantas, which faced fierce competition in the early 2000s from an Australia-based low-cost carrier. A review of previous low-cost carrier launches by other incumbents that had failed quickly revealed the underlying problem: The legacy carriers were trying to avoid disturbing their core. Qantas’s board decided not to make the same mistake. It set about building Jetstar as a completely new low-cost carrier that would be as separate and independent as possible from Qantas’s core business and even compete with it in some ways. This meant recruiting Jetstar’s management externally; basing the company in Melbourne rather than Sydney; having no direct check-through of baggage between airlines, no shared terminals, and no access to the Qantas loyalty or reservation systems; and often using different — lower-cost — airports.

The article added that, crucially, Qantas accepted that the parent business would lose some revenues to its new offspring. Point-to-point routes that were less profitable for Qantas were reallocated to Jetstar. The Sydney to Melbourne trip — one of the world’s busiest domestic routes — was shared, with Jetstar’s flights timed to suit cost-sensitive leisure travelers and Qantas’s scheduled for the less cost-conscious business market.

The outcome? Over 18 years, Jetstar has proven to be a highly successful airline that has taken market share profitably from Qantas and the competition. Qantas itself flies fewer routes than before Jetstar came along, but those routes are more profitable. By thinking like a disruptor, Qantas tapped into a massive low-cost market that might otherwise have gone elsewhere. It was a brave decision by Qantas’s leaders — and a smart, value-adding one for the group’s future.

Photo By: Canva

The article points out that a private equity player buys dirty, sells clean, and extends the value creation ecosystem. Thinking like an ESG disruptor can be pivotal in deriving value from M&A. Consider a bid that’s currently underway from a private equity investor for a listed financial institution facing significant regulatory and reputational issues. The target has struggled for some years. First, it couldn’t change fast enough in response to shifts in the market for its financial products. For example, it was aware of changes to the regulation of advice, but its internal controls were not strong enough to adequately monitor compliance with the regulation, triggering a series of private litigations. Then, its group executive and board misread the sentiment of leadership and a shift in community expectations, and this issue bubbled up into the public domain, affecting the company’s reputation. The resulting slide in the company’s valuation attracted the attention of private equity investors, one of whom tabled a takeover offer with a control premium effectively funded by removing the overhang of anticipated future regulatory actions. It’s a strategy sometimes characterized as “buy dirty, sell clean.”

The bid is ongoing. For the potential acquirer, the key questions are what issues it can solve within the targeted acquisition to rebuild enterprise value, and in what time frame. Its four-step strategy is designed to harness disruption by starting from a blank slate:

- First, clarify the value proposition for the financial advice business.

- Second, address the regulatory compliance issues, thus helping to rebuild trust and remedy the 20 percent discount against fundamental value created by the reputational concerns.

- Third, tackle operational complexity to reduce the cost base.

- Fourth, divest some parts of the group’s portfolio to realize additional value.

The PwC article points out that this strategy is aimed at “cleaning up” the core of the business and making it fit to be run profitably with increasing enterprise value — powered by societal impacts, reputation, and trust in the broad value creation ecosystem.

In the next article I will focus on the final three elements.

The Mystery Practitioner is an industry commentator that focuses on the shifting dynamics and innovative thinking that BRPs and turnaround professionals will need to embrace in order to achieve success in their businesses.